The state's embattled child protection agency lacks a clear mission, Gov. Charlie Baker said Monday while ordering new policies in the wake of high-profile cases like that of Bella Bond, the toddler known for months as Baby Doe after her remains washed up on the Boston Harbor shoreline.

The steps are aimed at reducing caseloads and updating the way the Department of Children and Families evaluates and prioritizes allegations it receives of abuse and neglect, the Republican said. He added that some basic procedures at the agency hadn't been changed in more than a decade despite a series of critical reports and studies.

The result was "mission confusion" for social workers in the field and their supervisors, he said.

"We are simplifying and focusing the mission: keep kids safe," he said.

Baker made ongoing problems at DCF a core issue during his campaign to become governor last year, but he has since faced some of the same questions as his predecessors.

The agency has said it twice intervened with Bella's family when she was an infant, once in 2012 and again in 2013 for reasons of neglect. Both cases were closed within a matter of months. DCF also revealed that it had removed two other children from Bella's mother between 2001 and 2007.

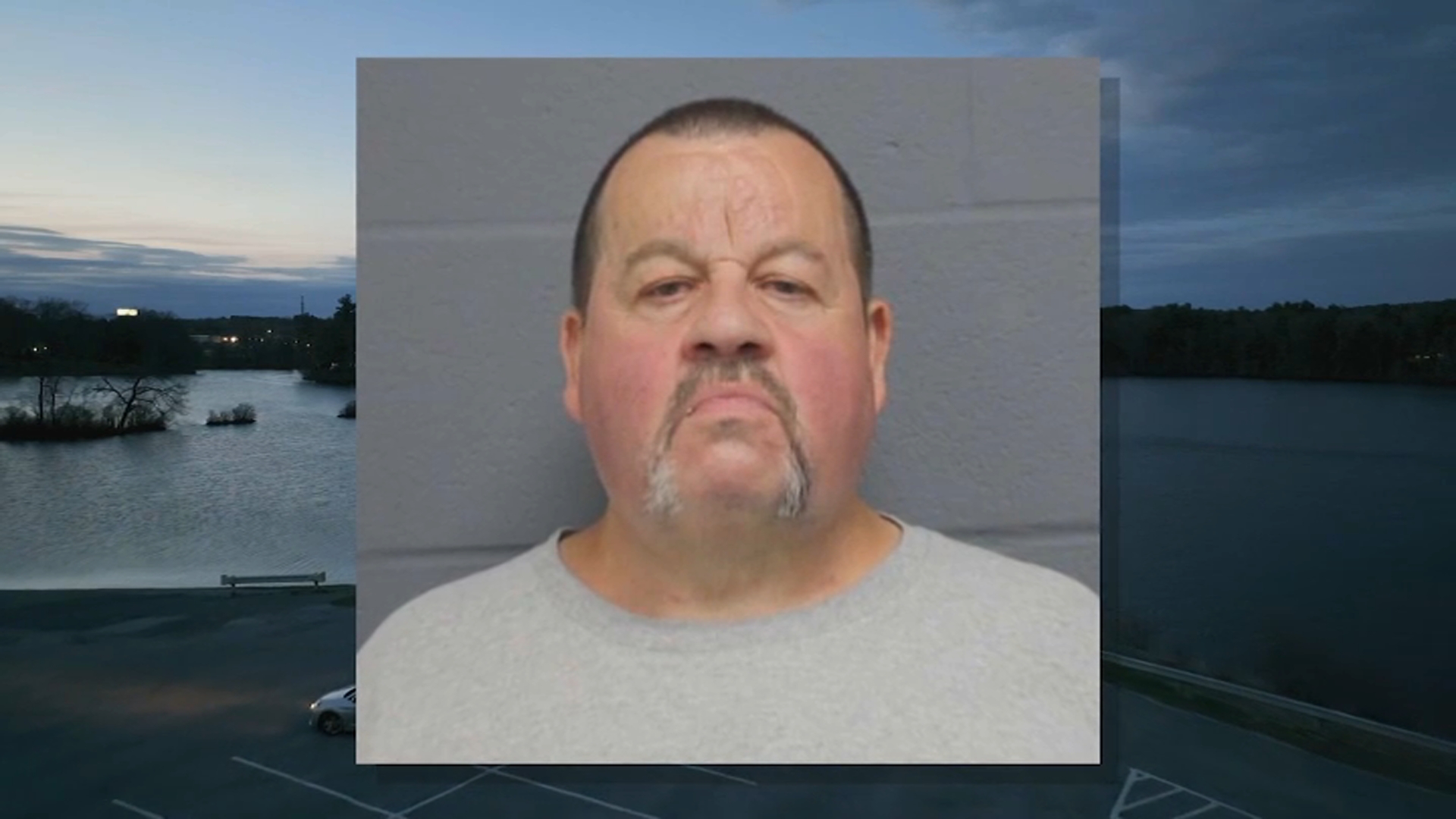

Rachelle Bond was charged as an accessory after the fact in the 2-year-old's death, and Bond's boyfriend, Michael McCarthy, is charged with murder.

Local

In-depth news coverage of the Greater Boston Area.

A key question that emerged is whether social workers who investigated Bella's care were aware that the older children had been removed from the mother, and if that information should have reflected on the decisions to close the 2012 and 2013 cases.

Linda Spears, the DCF commissioner, said Monday she could not immediately answer those questions, citing confidentiality rules and an ongoing investigation by the state's Child Advocate.

Baker said the agency was developing a new standardized policy for assessing the level of risk facing a child. It will include a mandatory review of every family member's history with DCF, "including parental capabilities," and criminal background checks.

Asked later if the policies might result in more children being taken from their biological parents, the governor said he did not necessarily expect that to be the case but believed the changes would clarify that the safety of children always takes precedence.

Peter MacKinnon, head of a union that represents about 2,900 DCF employees, praised Baker's reform efforts while criticizing previous "patchwork attempts at reform that did little more than create a state of misguided directives, confusing memos and disjointed half-completed policies."

Frontline social workers were left with often confusing and contradictory directives and an ever-increasing caseload that produced what he called "drive-by social work."

Baker said the state was committed to ramping up the hiring of new social workers with the goal of reducing the average number of cases being handled by a single social worker at any given time from the current 20.7 to 18. But he also acknowledged that DCF was a long way from reaching that goal, and would not commit to additional state funding beyond the $35 million increase the agency received in the current fiscal year budget.

Democratic legislative leaders endorsed Baker's actions but did not rule out further moves by the Legislature aimed at strengthening DCF. Senate President Stan Rosenberg, who grew up in the state's foster care system, said the agency had been hurt by "years of underfunding."