- President Joe Biden's decades of experience in the Senate and his faith in compromise were rewarded when his $1 trillion infrastructure bill passed the Senate with rare bipartisan support.

- To achieve the bill's passage, the White House and Democrats benefited from months of careful strategy plus a little bit of dumb luck.

- "The lesson learned is being willing to talk and listen," Biden said Tuesday. Listening "is a part of democracy," he added.

WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden's decades of experience in the Senate and his personal faith in compromise were rewarded Tuesday, when his $1 trillion infrastructure bill passed the Senate in a rare bipartisan vote of approval.

The vote was the culmination of months of intense work by the White House and a bipartisan group of 10 senators, who negotiated a dizzying series of compromises that maneuvered the bill through a deeply divided Senate.

In the end, 19 Republicans crossed party lines Tuesday and joined all 50 Democrats in voting for major new investments in roads, bridges, broadband access, public transit and green energy.

Get Boston local news, weather forecasts, lifestyle and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC Boston’s newsletters.

The vote was a mammoth vindication for Biden's belief that despite its arcane rules, the Senate still fundamentally works the way it's supposed to — a belief not shared by many of Biden's fellow Democrats.

To make the Senate work, however, a remarkable set of circumstances had to come together in the past few months, a perfect storm of politics and policy.

A career in the Senate pays off

Money Report

In the center of all this was Biden himself, a career senator who aides say is fully aware that the success of his first term as president is inextricably tied to the success of this infrastructure bill.

Throughout the spring and summer, Biden traveled across the country showcasing how the legislation would improve people's lives.

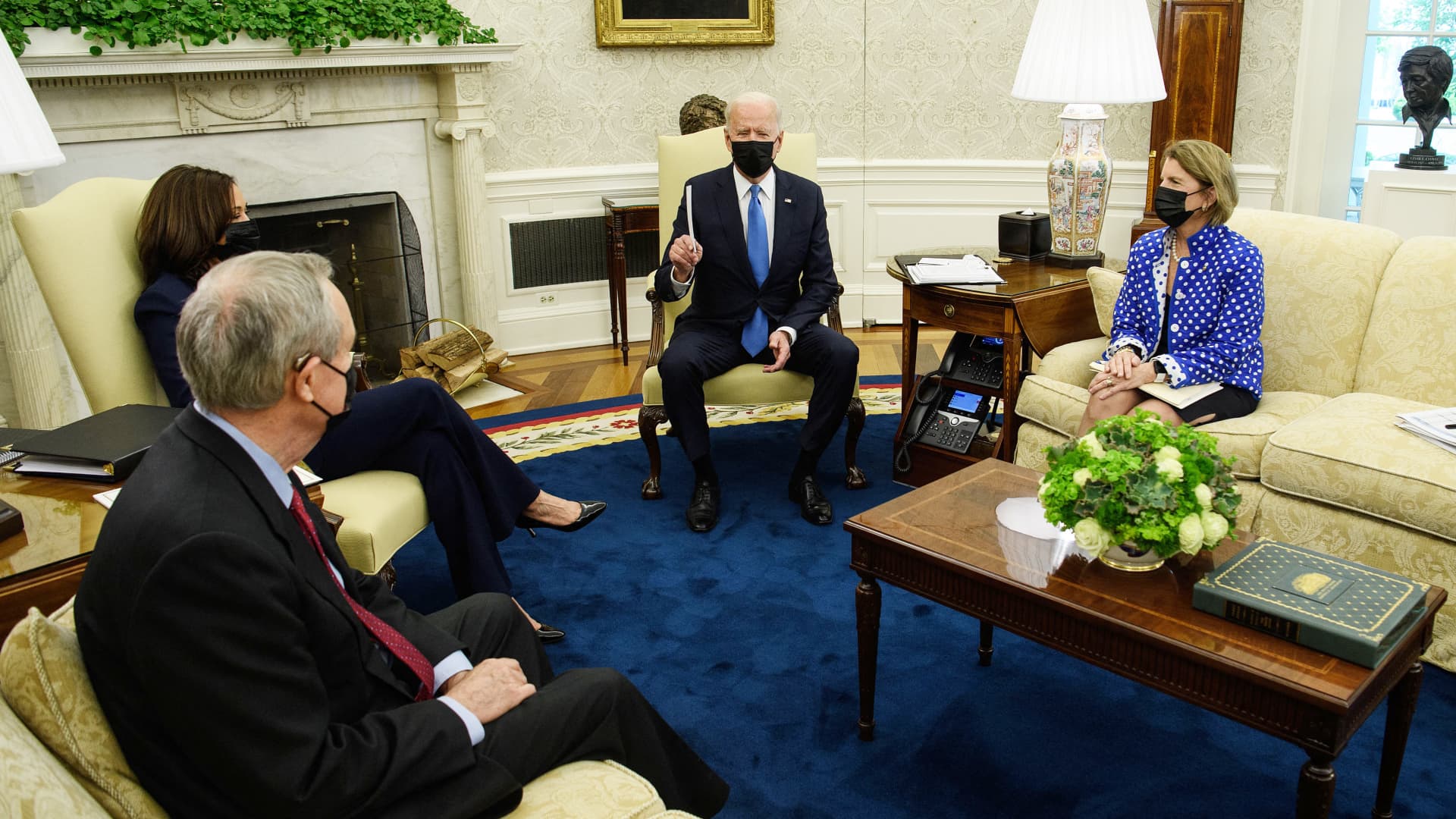

Back in Washington, Biden personally waded into the legislative drama at decisive moments.

In May and June, the president hosted both Republican and Democratic senators at the White House for candid, private meetings in the Oval Office to talk about what they needed to see in the bill in order to support it.

Some senators needed extra hand-holding. Biden met at least three times one-on-one with Arizona's Kyrsten Sinema, a centrist Democrat who refused to support the legislation unless it was passed with bipartisan support.

Sinema would eventually become the de facto leader of a small group of Senate Democrats who negotiated directly with Republicans and the White House.

But early on, her refusal to support Democrats' proposals to scrap the 60-vote threshold in the Senate and pass the infrastructure bill along party lines made her seem more like an obstacle to the legislation than an asset.

After one of her early meetings with Biden, Sinema said that she and the president had discussed, among other things, the importance of rural broadband expansion to her home state of Arizona.

The bill that passed on Tuesday provides $65 billion to expand broadband access to underserved communities.

The Bernie factor

But it wasn't just the centrists who Biden courted.

In mid-July, the president met at the White House with progressive Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., his onetime rival for the Democratic presidential nomination.

At the time, Sanders, who chairs the powerful Senate Budget Committee, was publicly calling for a social safety net package totaling $6 trillion. This was nearly twice the figure the White House was working with, and far more than most moderate Democrats could support.

Outside of Washington the idea of a $6 trillion, Democrats-only spending bill was politically poisonous, however, and fed right into the Republican stereotype of Democrats as big government liberals who run up the debt.

For Democrats seeking reelection next year, a vote in favor of a $6 trillion spending bill seemed like political suicide.

Biden needed to reach an understanding with Sanders quickly, or risk fracturing the fragile coalitions holding Democrats together.

Sanders also wanted something specific from the White House: The president's support for a plan to expand Medicare coverage to include dental, vision and hearing care.

A day after Sanders and Biden met on July 12, Democrats unveiled their long-anticipated social safety net plan.

Most of the plan fulfilled specific promises that Biden had made to voters during his 2020 presidential campaign. But there was one last-minute addition: Medicare coverage for dental, vision and hearing care.

On Tuesday, Biden said there were lessons to be drawn from how the infrastructure bill had been negotiated.

"The lesson learned is being willing to talk and listen," he told reporters at the White House. "Listen. Call people in. And I think the lesson learned is exposing people to other views."

"That's why, from the beginning, I've sat with people and listened to their positions — some in agreement with where I am and some in disagreement. So I think it's a matter of listening; it's part of democracy," said Biden.

Republican retirements

As Biden and his fellow Democrats worked to unite the party behind the infrastructure bill and its sister bill, the $3.5 trillion social safety net expansion, their task was made easier by unique dynamics playing out within the Republican caucus.

One was an unusually large number of Republican retirements announced in the Senate this cycle.

Typically, a senator up for reelection is under constant pressure, first to win over his party's base in order to survive a primary challenge, and then to win support statewide in order to win a general election.

But a retiring senator faces no such pressures. Retiring senators are free to vote their consciences, without worrying about whether those votes could hurt them on Election Day.

Of the five Republican senators who have announced plans to retire next year, three of them crossed party lines to support the infrastructure bill.

Retiring Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio led the GOP negotiating team, and did more than almost anyone to get the deal over the finish line.

Two other retiring Republicans, Richard Burr of North Carolina and Roy Blunt of Missouri, also threw their support behind the deal at crucial moments.

Burr signed on in mid-July, helping to answer the question of whether a deal that had been reached by a small cadre of senators could win over a broader coalition.

Blunt voted for the bill in its first big test, a procedural vote in late July to begin formal debate on the legislation.

But there is one Republican whose support for the deal did more than even Portman's ensure the infrastructure bill's bipartisan success: Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell.

McConnell's motivation

During his nearly 15 years as leader of the Senate Republican caucus, McConnell has embraced his reputation as a grim reaper for Democrats' pet legislation, always ready to ring the death knell.

But this time around, McConnell held back.

Instead of blocking the infrastructure bill from the outset, as many expected him to do, McConnell tacitly let the negotiations proceed. He also left the door open to approving a bipartisan deal, and greenlighted Republicans to vote for one.

As the summer wore on and the bill advanced through the Senate, the question of why McConnell didn't kill it became a Washington parlor game.

There are several factors likely at play here.

One is that infrastructure is universally popular with voters, and McConnell knows that as well as anyone.

"He's a very pragmatic person. I think he knows that everybody sort of wins if it's true, hard infrastructure," said Sen. Kevin Cramer, a North Dakota Republican, in a recent interview with the Associated Press.

Another boon for the deal is the fact that residents of McConnell's home state of Kentucky will likely see outsized benefits from its provisions, such as federal road projects and expanded rural broadband funding.

Yet another element working in the bill's favor is the bigger debate going on within the Senate over the fate of the filibuster, the 60-vote threshold needed to advance most legislation through the chamber.

Biden has resisted mounting calls by progressive Democrats to eliminate the filibuster, which critics say is an outdated and fundamentally unfair threshold.

McConnell, like Biden, believes the filibuster is crucial to what makes the Senate a more deliberative and cooperative body than the House. The last time Republicans held the Senate majority during President Donald Trump's term, McConnell steadfastly refused Trump's demands that he scrap the filibuster.

For McConnell, letting the infrastructure bill pass with more than 60 votes "is a good demonstration that he can preserve the filibuster and still have meaningful, bipartisan legislation," Cramer said to the AP.

"And at the end of the day, he's got a constituency back in Kentucky that probably looks pretty favorably on it."