- The prospect of a Fed triple threat of tightening sent the market into a tailspin on Wednesday.

- Central bankers indicated in their December minutes that they expect not only to raise rates and taper asset purchases soon — but also could be teeing up a balance sheet reduction.

- That's important for investors because central bank liquidity has helped underpin markets during the Covid tumult.

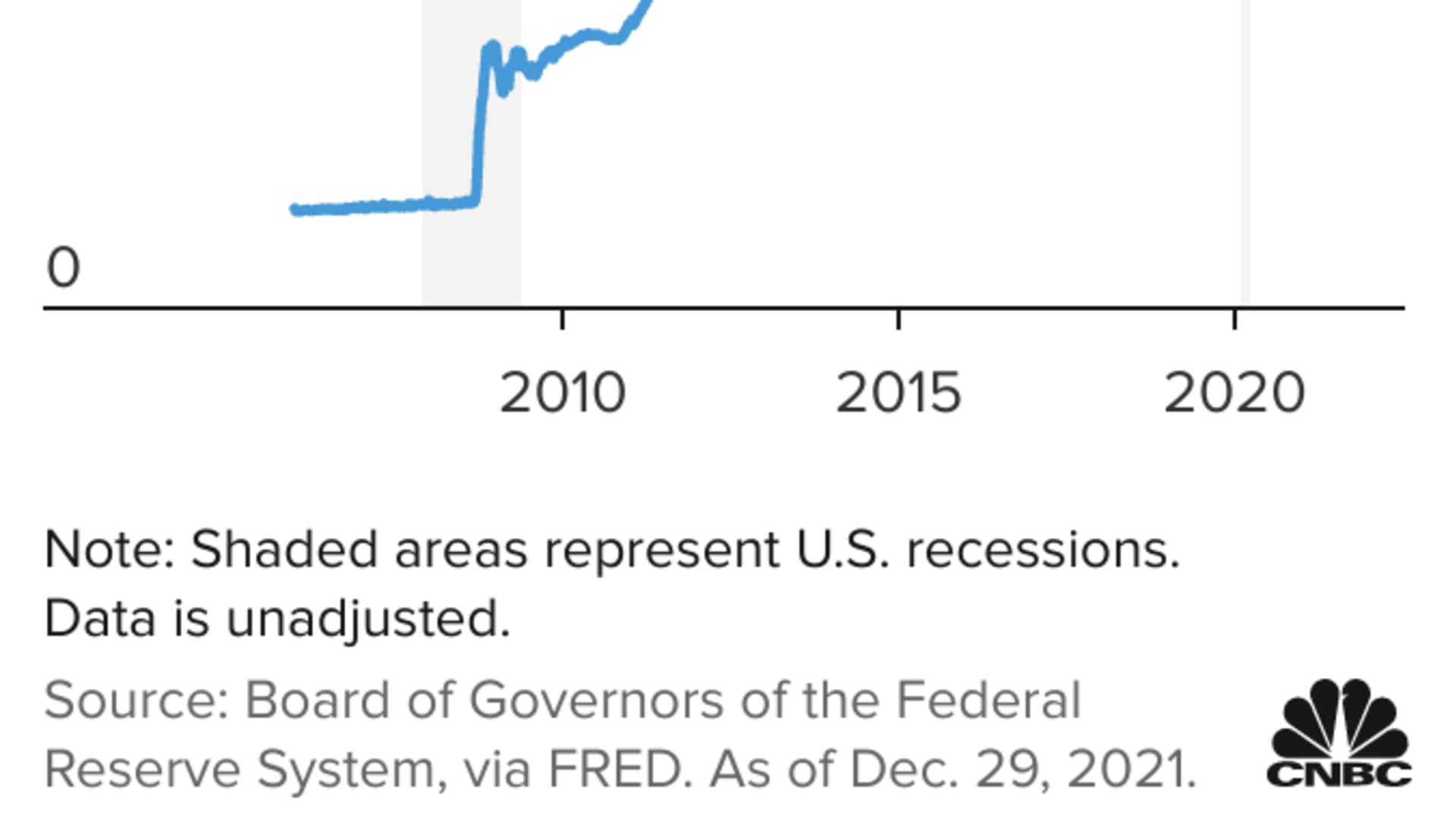

Investors have been preparing for the Federal Reserve to start hiking interest rates. They also know the central bank is cutting the amount of bonds it buys each month. On top of that, they figured, eventually, the tapering would lead to a reduction in the nearly $9 trillion in assets the Fed is holding.

What they didn't expect were all three things happening at the same time.

Get Boston local news, weather forecasts, lifestyle and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC Boston’s newsletters.

But minutes from the Fed's December meeting, released Wednesday, indicated that may well be the case.

The meeting summary showed members ready to not only start raising interest rates and tapering bond buying, but also being prepared to engage in a high-level conversations about reducing holdings of Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities.

While the moves are designed to fight inflation and as the jobs market heals, the jolt of a Fed triple threat of tightening sent the market into a tailspin Wednesday. The result saw stocks give back their Santa Claus rally gains and then some as the prospect of a hawkish central bank cast a haze of uncertainty over the investing landscape.

Money Report

Markets were mixed Thursday as investors tried to figure out the central bank's intentions.

"The reason the market had a knee-jerk reaction yesterday was it sounds like the Fed is going to come fast and furious and take liquidity out of the market," said Lindsey Bell, chief market strategist at Ally Financial. "If they do it in a steady and gradual manner, the market can perform well in that environment. If they come fast and furious, then it's going to be a different story."

Fed officials said during the meeting that they remain data-dependent and will be sure to communicate their intentions clearly to the public.

Still, the prospect of a much more aggressive Fed was cause for worry after nearly two years of the most accommodative monetary policy in U.S. history.

Bell said investors are likely worrying too much about policy from officials who have been clear that they don't want to do anything to slow the recovery or to tank financial markets.

"The Fed sounds like they're going to be a lot quicker in action," she said. "But the reality is we don't honestly know how they're going to move and when they're going to move. That's going to be determined over the next several months."

Clues coming soon

Indeed, the market won't have to wait long to hear where the Fed is headed.

Multiple Fed speakers already have weighed in over the past couple days, with Governor Christopher Waller and Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari taking a more aggressive tone. Meanwhile, San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly said Thursday she thinks the start of balance sheet reduction isn't necessarily imminent.

Chairman Jerome Powell will speak next week during his confirmation hearing, and a second time this month following the Fed meeting on Jan. 25-26, when he may strike a more dovish tone, said Michael Yoshikami, founder and chairman of Destination Wealth Management.

One big factor Yoshikami sees is that while the Fed is determined to fight inflation, it also will have to deal with the negative impact of the omicron variant.

"I expect the Fed to come out and say everything is based on the pandemic blowing over. But if omicron really does continue to be a problem for the next 30 or 45 days, it is going to impact the economy and might cause us to delay raising rates," he said. "I expect that commentary to come out in the next 30 days."

Beyond that, there are some certainties about policy: The market knows, for instance, that the Fed starting in January will be buying just $60 billion of bonds each month — half the level it had been purchasing just a few months ago.

Fed officials in December also had penciled in three quarter-percentage-point rate hikes this year after previously indicating just one, and markets are pricing in close to a 50-50 chance of a fourth hike. Also, Powell had indicated that there was discussion about balance sheet reduction at the meeting, though he seemed to play down how deeply his colleagues delved into the topic.

So what the market doesn't know right now is how aggressive the Fed will be reducing its balance sheet. It's an important issue for investors as central bank liquidity has helped underpin markets during the Covid tumult.

During the last balance sheet unwind, from 2017 until 2019, the Fed allowed a capped level of proceeds from its bond portfolio to run off. The cap started at $10 billion each month, then increased by $10 billion quarterly until they reached $50 billion. By the time the Fed had to retreat, it had run off just $600 billion from what had been a $4.5 trillion balance sheet.

With the balance sheet now approaching $9 trillion — $8.3 trillion of which is comprised of the Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities the Fed has been buying — the initial view from Wall Street is that the Fed could be more aggressive this time.

'Uncharted waters'

Estimates bandied about following Wednesday's news ranged from maximum caps of $100 billion from JPMorgan Chase to $60 billion at Nomura. Fed officials have not specified any numbers yet, with Kashkari earlier this week only saying that he sees the end of the runoff still leaving the Fed with a large balance sheet, probably bigger than before Covid.

One other possibility is that the Fed could sell assets outright, said Michael Pearce, senior U.S. economist at Capital Economics.

There would be multiple reasons for the central bank to do so, particularly with long-dated interest rates so low, the Fed's bond profile being relatively long in duration and the sheer size of the balance sheet — almost twice what it was last time around.

"While longer term yields have rebounded in recent days, if they were to remain stubbornly low and the Fed is faced with a rapidly flattening yield curve, we think there would be a good case that the Fed should supplement its balance sheet runoff with outright sales of longer-dated Treasury securities and MBS," Pearce said in a note to clients.

That leaves investors with a multitude of possibilities that could make navigating the 2022 landscape difficult.

In that last tightening cycle, the Fed waited from the first hike before it started cutting the balance sheet. This time, policymakers seem determined to get things moving more quickly.

"Markets are concerned that we've never seen the Federal Reserve both lift interest rates off zero and reduce the size of its balance sheet at the same time. There was a two-year gap between those two events in the last cycle, so it is a valid concern. Our advice is to invest/trade very carefully the next few days," DataTrek co-founder Nick Colas said in his daily note Wednesday evening. "We're not predicting a meltdown, but we get why the market swooned [Wednesday]: these are truly uncharted waters."