- For the first time, the quadrennial U.N.-backed Montreal Protocol assessment report included an entire chapter addressing stratospheric aerosol injection, more colloquially called solar geoengineering.

- It's a way to cool the atmosphere by injecting sunlight-reflecting particles, similar to what happens naturally with volcanic eruptions.

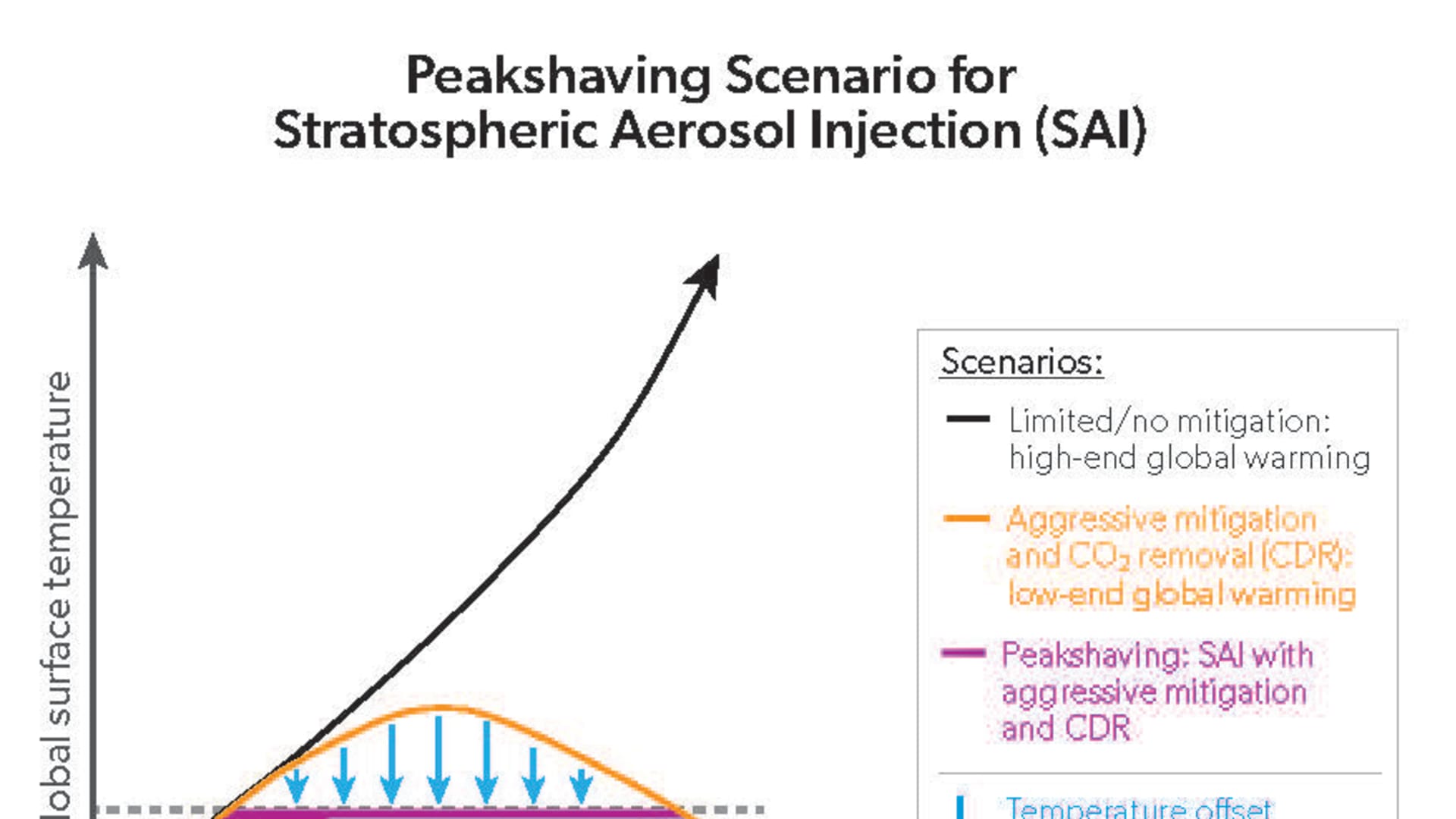

- A simple concept graph included in the report visually represents the way in which solar geoengineering ought to be thought of — as a temporary stopgap measure.

The world is not reducing emissions fast enough to mitigate the most deadly effects of climate change, so it's time to study temporary methods to cool the Earth by blocking some of the sun's rays, according to an internationally recognized group of scientists.

Every four years, scientists backed by the United Nations put out a report assessing the progress of the Montreal Protocol, a landmark 1989 environmental treaty that regulated chemicals that harmed the ozone layer. For the first time ever, the report has an entire chapter addressing stratospheric aerosol injection, more colloquially called solar geoengineering.

It's a way to cool the atmosphere temporarily by injecting sunlight-reflecting particles of sulfur dioxide, or perhaps another substance, into the upper atmosphere, similar to what happens naturally with volcanic eruptions.

Get Boston local news, weather forecasts, lifestyle and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC Boston’s newsletters.

The idea has been mentioned in earlier reports, but "what's different this time is the prominence," explained David Fahey, one of the co-chairs of the scientific assessment panel.

The pressing question regarding stratospheric aerosol injection is whether this kind of solar geoengineering is more damaging to the Earth than the climate change it would temporarily mitigate. There's no simple answer, which is why more study is required.

"It depends on: What are you injecting? What altitude you're injecting it. How much you're injecting. What latitude are you injecting? What time of year are you injecting? And are you doing more than one injection?" Fahey told CNBC. Generally speaking, conversations about releasing particles into the stratosphere are referring to sulfur dioxide, but there are no clear answers to the other questions.

Money Report

"We're actually advancing the ball a bit here by having the first full chapter in this framework where every nation in the world is at the table," Fahey said. "'It depends,' is a really, really important message on this topic at this stage."

A chart in the report summarizes how the scientists believe geoengineering should be considered — not as a solution to climate change, but as a way to lower temperatures temporarily. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions will eventually work to slow global warming, but that's a very slow process. Releasing sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere is fast and cheap compared to more long-term solutions.

"The world is kind of in the denial stage of what's likely to actually happen," Fahey told CNBC. And right now, "there is no real commitment on the part of the world to turn the black line into the orange line," he said, referring to the chart. "The big overlay is: you're on the black curve, buddy. Not on the orange curve."

To bring global temperatures down quickly, "the only button that we can push — that we know about — is climate intervention," Fahey said.

There are a lot of uncertainties about the bad effects of solar geoengineering. It may damage the ozone layer, cause respiratory problems and generate acid rain. But scientists do know that it will reduce temperatures because of the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991. In the 15 months after the volcano eruption, the average global temperature was about 1 degree Fahrenheit lower, according to NASA.

That's why Fahey believes scientists should be studying the issue carefully in an international forum, like the Montreal Protocol or the U.N.'s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Fahey told CNBC.

For the co-founders of the startup, Make Sunsets, which aims to begin testing solar geoengineering with three balloon flights in January, the urgency to mitigate global warming supersedes the remaining uncertainty about the negative consequences of solar geoengineering.

"My comment about that to myself when I first discovered this was, in so many words, 'Let the games begin,'" Fahey told CNBC. "In a world in which there is no forum to discuss the science or the governance or the ethics, now you have people simply doing what they want to do," Fahey said.

Technically, the Make Sunsets approach is not sophisticated, and the scale of the planned tests are so small that they are relatively insignificant. But at least the startup is getting people talking, and that's "probably not a bad thing overall" because "it doesn't have enough attention in the world at the moment," Fahey told CNBC.