For Teresa Drisko and Kathy Kelly, the news story hit home. The neighbors in Quincy, Massachusetts, thought the story in February of a man accused of stabbing a woman in a library in Winchester sounded too familiar for comfort: the red flags, the calls to police, the inability of anybody to do anything.

The women are worried about a man in their neighborhood — his outbursts, his repeated hospitalizations and escalating behavior leave them feeling threatened.

They're worried about a state mental health system that seems incapable of dealing with mentally ill people with treatment and respect while protecting everyone in the community.

People struggling with mental health issues are far more likely to be the victim of violence than the perpetrator. But when their issues, and a failing system, disrupt a community, residents, police and state leaders seem able to do little more than ask about what be can be done.

"What do we need to do? Who do we go to? Is there anyone we go to? We called the cops, we reached out to the mayor," Kelly said. "I don't care who helps us. Somebody needs to help us."

NBC10 Boston will not identify their neighbor, an adult struggling with mental illness and with no criminal record. He did not return our calls.

But Kelly and Drisko said the man screams outside their homes, and has left his trash on porches, keyed cars and slashed tires. After conversations with the man, residents have found their houses egged.

"I don't want to be a victim," Drisko said. "I don't want to be that person in the story."

Drisko's 5-year-old dog, Max, was poisoned, according to her veterinarian. Max had to be euthanized.

"It's awful. I'm afraid to be home," Drisko said. "Max was my protector. He was a 95-pound dog that would bark if somebody was around, and I've had to put security cameras in. I'm having floodlights installed now. I've always felt bad. But now, when I'm more concerned about my safety, it's hard to feel bad anymore."

Local

In-depth news coverage of the Greater Boston Area.

Max's death was among a string of escalating incidents in recent weeks that worry the neighbors and have caught the attention of Quincy Police.

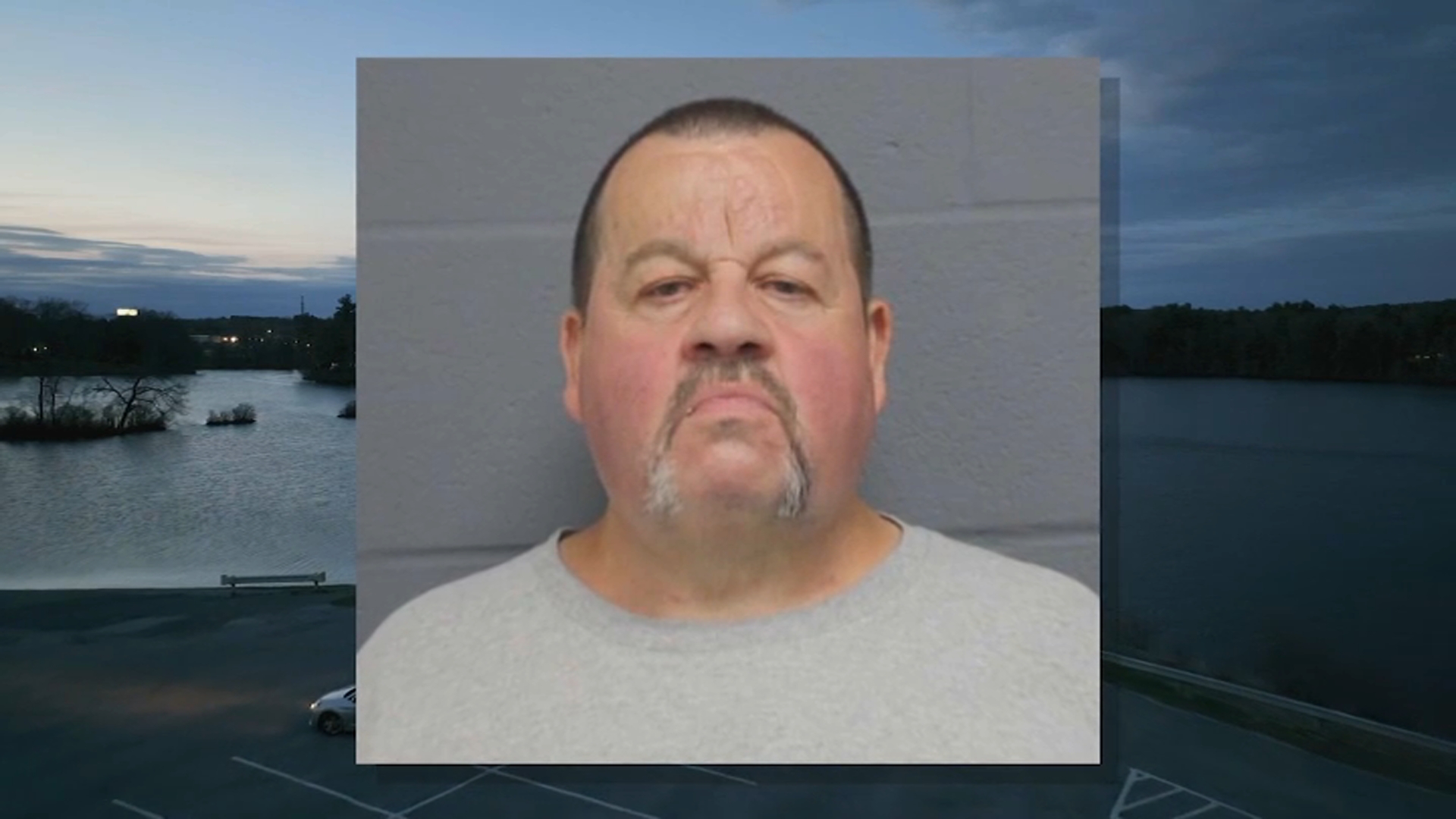

"They're escalating as far as the level of violence or the level of threat and intimidation, so it becomes troubling for us," Quincy Police Chief Paul Keenan said. "It's unfortunate that it has taken such a toll on the neighbors. The mental health system is such that sometimes, there's gaps in the treatment and gaps in the care. And the neighbors sometimes pay a price for that."

The man has a decade-long history with police. The allegations range from disturbing the peace to destruction of property to assault and battery.

Twice, officers said, they have found him yelling at people in the street with a bat or wooden club, threatening he either had or would get a gun. Police have never found a gun, and after each arrest, he is diverted to mental health services and later released. It is a pattern strikingly similar to Winchester.

Police who believe "that failure to hospitalize a person would create a likelihood of serious harm by reason of mental illness may restrain such person and apply for the hospitalization of such person for a three-day period at a public" or private mental health facility, according to state law. That process is called "sectioning," and a judge needs to sign off.

But even when they successfully section someone, privacy protections keep police from knowing what happens next.

"The courts lose control. We lose control," Keenan said. "They go into the mental health system and then it's very subjective in what medication they take and how long they stay."

The chief said police often have to wait until the person does something criminal, because then the suspect can be required to get services in jail. He called that a tragedy.

Mental health advocates said even though some people might fall through the cracks, their rights must be protected.

"If a person is not deemed a danger to himself or others, then you just have to cope," said Phillip Kassel, an attorney and the executive director of the Mental Health Legal Advisors Committee, a group created by the state legislature to protect the legal rights of people involved in mental health programs.

Quincy has an in-house mental health professional that goes out on calls, helps police manage relationships with people suffering from mental health issues and helps those people get care. It is unclear if she was engaged in this case.

The state previously operated a number of public psychiatric hospitals, but shut most them down years ago. The intention was to help those patients live independently. But, by and large, the state took those savings and spent them on other things.

"Instead of saying, 'OK, we're going to provide a variety of services for people in the communities where they live, and we hope they will stay,' the money was diverted," Kassel said. "The services are not as available as they should be. And a variety of services isn't available. We've only really started to try to catch up lately."

Massachusetts ranks 23rd in per-capita spending on mental health, below the national average and behind most New England states, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

"Would I like to be number one? Of course," said state Rep. Patricia Haddad, D-Somerset. "But the realities, again, of a budget are that it's a chip-chip-chip in programs, in ways to respond, in training, in our reactions overall."

Advocates say after chronic underfunding of the state Department of Mental Health, the state has significantly boosted the budget this year, investing in community programs, peer counseling and housing.

But Kassel is not optimistic.

"We're not in the optimism business, I'm afraid," he said. "But I think it's hopeful. And I don't think I can go beyond that. I'll believe it when I see it."

The neighbors in Quincy hope they see change, because they are worried for everyone.

"He needs your help," Kelly said, referring to their neighbor. "As well as us."

A 22-year-old medical student was stabbed to death on Feb. 24 in the Winchester Public Library. The man accused in her murder, 23-year-old Jeffrey Yao, has a history with police and a number of warnings from neighbors, and school and police officials about his mental health.

Yao was arraigned for murder and ordered held without bail in February.