Don Deaver followed details of the destruction in Massachusetts from afar in Houston and struggled to find a comparison.

And that’s saying something for the natural gas expert, who spent more than three decades at Exxon. He’s also provided testimony as an expert witness in more than 100 natural gas investigations.

“I personally don’t know of an event that’s happened of this magnitude,” Deaver told the NBC10 Boston Investigators.

Like other experts who are scrutinizing the natural gas disaster across the Merrimack Valley, Deaver agrees the incident seems to be an obvious case of “over-pressurized” gas lines.

A similar tragedy played out in Chicago in 1992, when a natural gas disaster killed three people, sparked 10 fires, and destroyed 18 buildings.

“Like any piece of equipment, they can suddenly or catastrophically fail,” Deaver explained.

You’ve seen the warning signs on posts marking the location of gas transmission pipelines. Perhaps you’ve spotted the distribution facilities hidden in wooded areas of your neighborhood.

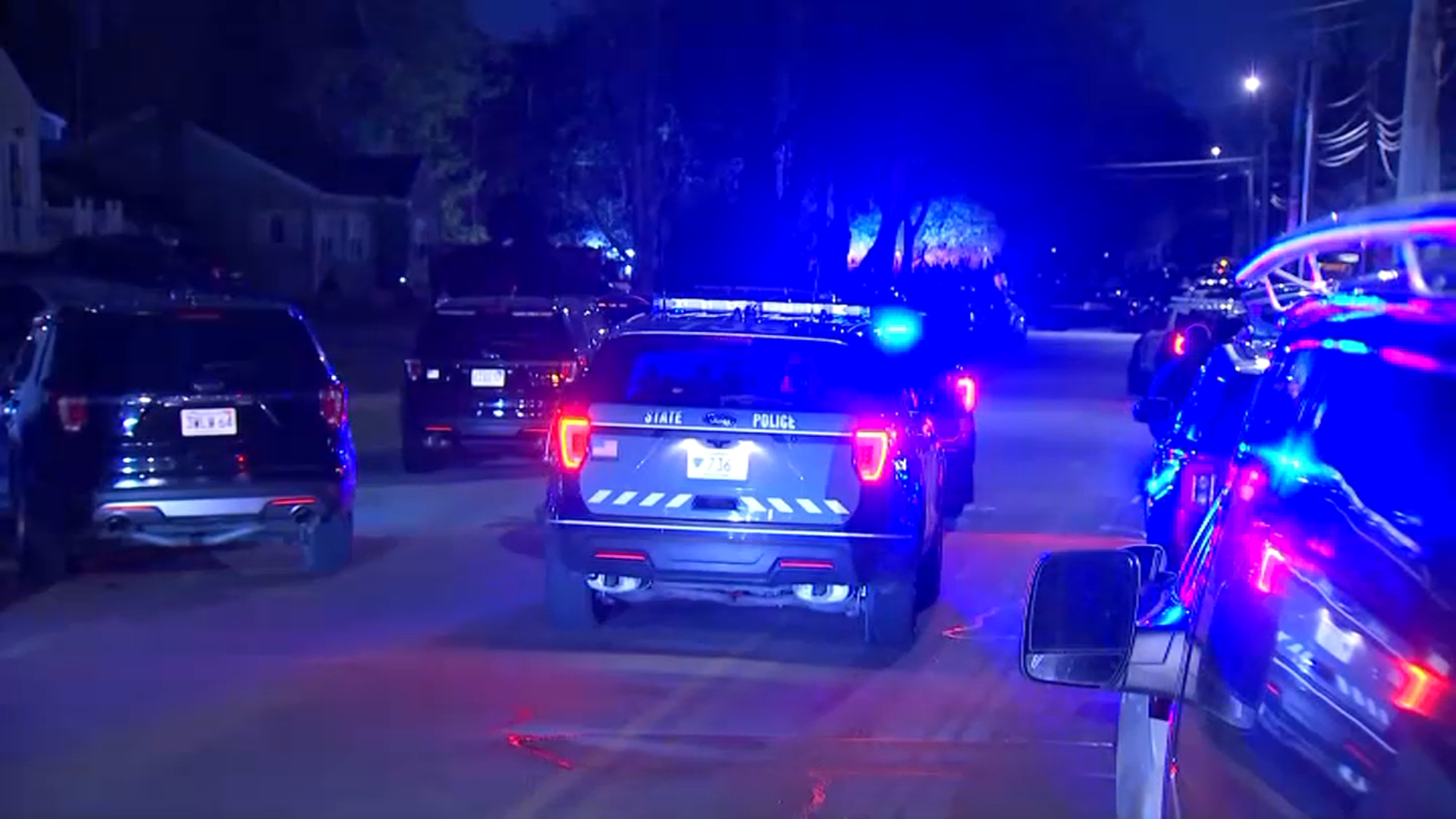

Local

In-depth news coverage of the Greater Boston Area.

But chances are, most people don’t think much about how natural gas gets from transmission stations to business and homes.

Deaver said gas travels quickly across the country in high-speed pipelines, usually with hundreds of pounds of pressure.

It then moves through a series of “step downs” at regulator stations. Think of those as gatekeepers that reduce the pressure to safer levels, likely to 60 psi as gas reaches neighborhood distribution systems, and eventually down to just .25 psi as it gets to home utility meters.

“So there could be a 4,000 to 1 range of pressure that’s in the transmission pipeline bringing gas to your area to your house where you’re using the gas,” Deaver said.

That’s why it’s easy to imagine why it’s so destructive if something fails, and that high-pressure gas somehow ends up in a neighborhood system.

“You can get something that hits the whole system and creates an incredible amount of leaks,” Deaver explained. “It can spread at the speed of sound, so it’s very devastating.”

Ryan Kath can be reached at ryan.kath@nbcuni.com. You can also follow him on Twitter or connect on Facebook.