- The U.S. economy has regained 12.5 million jobs since the jobs market crash in March and April of 2020.

- Still, nearly 9 million fewer Americans are working now than last February.

- While enthusiasm is high about an economic rebound later this year, the jobs market faces important concerns now.

- Job placement has focused on retraining workers, though a skills gap remains.

At any other time in U.S. history, creating 12.5 million jobs in nine months would be astonishing. But this is like no other time the nation has seen, and there remains much work to be done to get America back to work again.

January's nonfarm payrolls report served as a reminder of just how much.

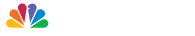

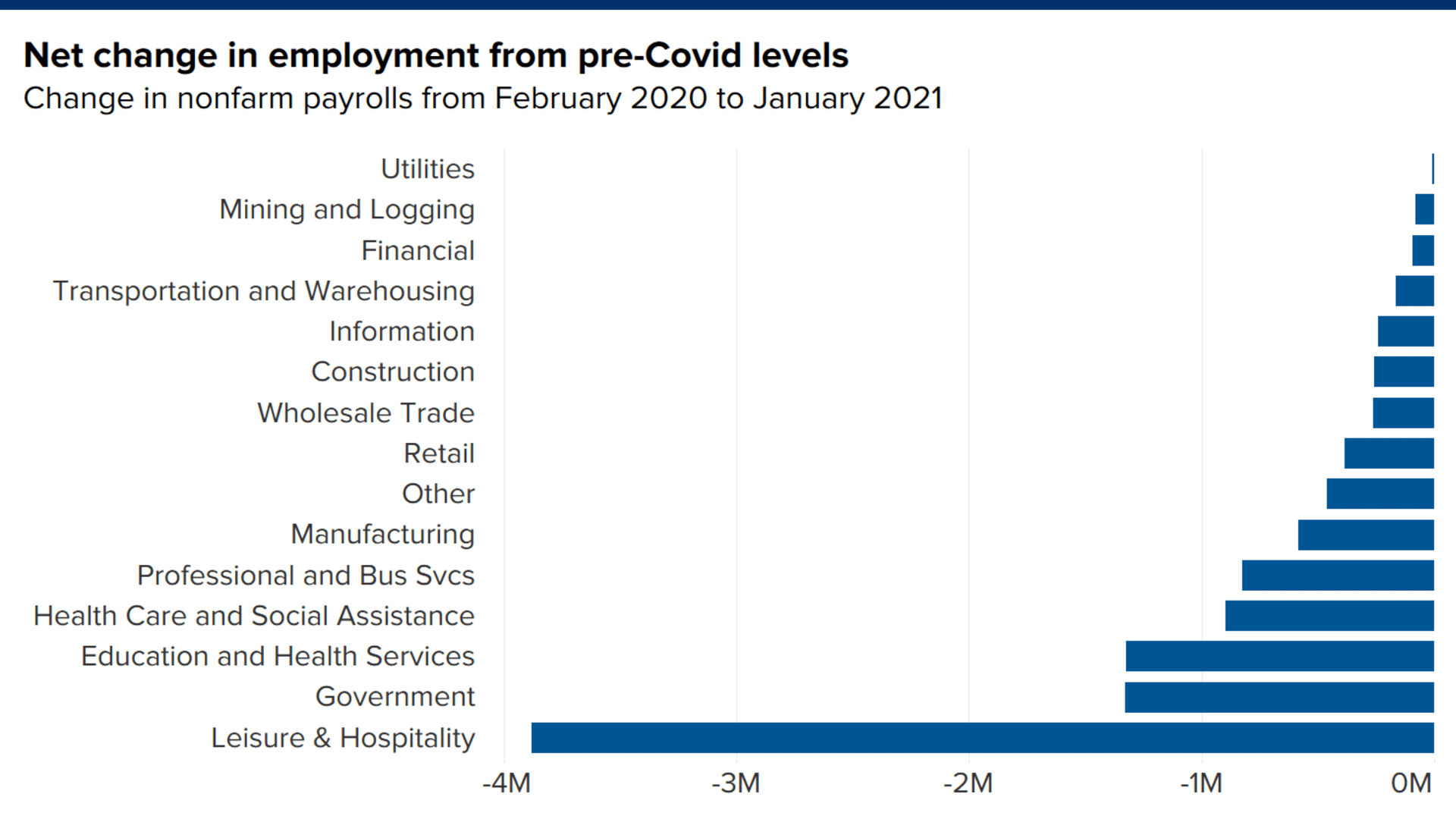

Private jobs grew by just 6,000 for the month as the hospitality, retail and health-care industries continued to cut workers. An increase in government hiring helped bring total payroll growth up to 49,000, but that still left the rolls of the total employed 8.7 million lower than in February 2020, just before Covid-19 officially became a pandemic.

"It's very clear our economy is still in trouble," President Joe Biden said Friday afternoon.

The president is correct in many respects.

Money Report

Though gross domestic product posted two quarters of solid growth to end the year, the $20.9 trillion U.S. economy closed 2020 $814 billion smaller than it was the previous year. On an annualized basis, GDP contracted 3.5%, the worst growth rate since the end of World War II.

Yet the mood around Wall Street and much of Main Street remains largely positive. Investors keep buying stocks, economists and Federal Reserve officials are talking about a powerful recovery later this year, and business and consumer sentiment measures remain strong. Goldman Sachs estimates that, thanks to the last round of checks, consumer spending actually rose to 103.9% of the pre-pandemic level in early January.

Corporate profits defied more muted analyst expectations, with 83% topping Wall Street estimates this quarter, and the Citi Economic Surprise Index, which measures data against expectations, continues to run around levels that would have been records before the pandemic as economists since June have underestimated the strength of the reports.

In the jobs world, there are plenty of high hopes outside the areas still bearing the worst of the employment crunch that happened in March and April of 2020.

While some industries, such as utilities and Wall Street-related positions, are close to their pre-pandemic levels, most are still a fairly far cry. Leisure and hospitality still faces a 15.9% unemployment rate and a 3.9 million jobs deficit that likely will never be closed.

But the agencies that have tried to engineer workers through the Covid-era employment paradigm report an active market, though one in which re-skilling is a priority for displaced employees of bars and restaurants, hotels and health-care facilities, and other pockets that have taken the worst hits.

"We are absolutely optimistic about the jobs market," said Karen Fichuk, CEO of Randstad North America, which deals with hundreds of thousands of clients navigating workforce challenges. "We have job orders and opportunities for job seekers that we need to fill."

This is, however, a segmented job market.

Millions of bartender and waitstaff jobs likely are never coming back, or not anytime soon. In their place are opportunities for e-commerce and transportation logistics. For those in the restaurant and hotel industry, they're finding they have skill sets that translate into nonclinical health-care jobs at call centers where they handle contact tracing and vaccination appointments.

"Those are roles where people who are in the hospitality and customer service industry can absolutely make that transition into newly created roles during the pandemic," Fichuk said.

Matt Godden, president and CEO at Seattle-based Centerline Logistics, is looking for workers in the marine transportation industry. Centerline operates at West Coast ports, providing fuel to ships that are bringing goods into the bustling Port of Long Beach near Los Angeles.

The firm employs 700 people and is looking to expand its workforce by about 10%, Godden said.

"We're really looking to the second half of the year being a pretty substantial uptick from what we were projecting the first half of the year to look like," he said. "Customers are really sticking with us. We see the market from our customers' perspective returning and coming back to something close to a pre-pandemic level."

Closing the gap

One persistently nettlesome issue for companies has been the skills gap – a phenomenon that began well before the pandemic and describes the difficulty of finding workers with the right qualifications. At one point during the economic expansion there were more than 1 million additional job openings than there were workers to fill them.

Though the ratio of openings to workers has swung in the other direction – about 4 million more jobless workers now than vacancies – the skills gap persists. Minneapolis Federal Reserve President Neel Kashkari earlier this week characterized the notion as "just a bunch of whining" by companies that can't find workers "at the wages they are used to paying," but employment specialists say the skills gap is real.

"The notion that CEOs or companies systematically would want to cut their labor costs at the expense of productivity just doesn't make much sense," said Michael Hansen, CEO at education technology company Cengage, who blames much of the problem on the education system. "The misalignment of incentives between the system and the labor market is something we are really focusing on."

One of the issues the system needs to address, Hansen said, is the idea that all students need to go to college. He also said schools are not providing adequate technology needed to adapt in the current workplace.

Like Randstad, Cengage is focusing on re-skilling workers to adapt to the changing face of the jobs market.

"What we have to do is make sure the education system is more digitally enabled," he said. "We need to move away from the notion that every job will require a college degree. We need to get more flexible."

The fiscal response

As the private sector looks to adapt, government is reacting by looking to channel more money at the issue.

Biden and congressional Democrats want to spend $1.9 trillion on direct payments to individuals, extended unemployment benefits, aid to cities and states and funding for Covid vaccine programs.

Republicans, looking to avoid more burden on strained national finances, are proposing $618 billion that likely would not meet Biden's approval as it does not include $1,400 individual payments on which the president said he will not compromise.

The difference between the two plans, though, may not be as much as the price tags indicate.

According to an analysis a few days ago by S&P Global Ratings, the economy returns to pre-pandemic levels by around the second quarter regardless of which plan gets approved. The Democratic plan would provide more juice in the near term, though it lacks supply side proposals like infrastructure spending that tend to have longer-term benefits, said Beth Ann Bovino, S&P's chief U.S. economist.

"It's certainly going to matter a lot to the people who need those benefit checks," Bovino said. "Spending on the stimulus is shorter-framed, meaning that it is largely demand-driven stimulus that is considered temporary. It ends. The bang for the buck ends when the stimulus ends."

Another part of the Biden plan is increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, something that in the past has drawn warnings as a job killer.

A Congressional Budget Office report from 2019 stated that taking the base wage up to that point would cost the economy 1.3 million jobs by 2025 and slightly lower aggregate household income. That study has been rebutted from various quarters, with some economists and think tanks saying the impact of raising the minimum wage is overstated.

Policymakers both in Congress and at the Federal Reserve remain committed to keeping the policy juice flowing until the jobs market and the rest of the economy is on a clearer path to recovery.

"The main goal for this is to keep people as whole as possible," Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic told CNBC a few days ago. "We know when you lose that many jobs, there are going to be holes to fill."