From complex COVID testing routines and GPS tracking to silence in the stands, U.S. athletes are bound for an unprecedented environment at the Tokyo Olympics.

“It's definitely going to be sad not having my family and friends in the stands like I had in Rio,” Olympic sabre fencer Eli Dershwitz said. “I was definitely using that as motivation, you know? That support system -- I was planning to have it as fuel during the competition.”

The 25-year-old Sherborn, Massachusetts, native is heading to the Olympics for the second time in his career, but the games will look much different than they did in Rio De Janeiro five years ago. Like everything else, the coronavirus pandemic is leaving its indelible mark on the Tokyo Olympics, posing added challenges for athletes and changing the experience in a profound way.

“I do understand that it's not going to be the same experience. But, you know, overall, I am appreciative of the Japanese government for hosting these games,” Dershwitz said. “There was a while where we, as athletes, didn't know if it was going to happen. You know, my whole life got put on hold for a year.”

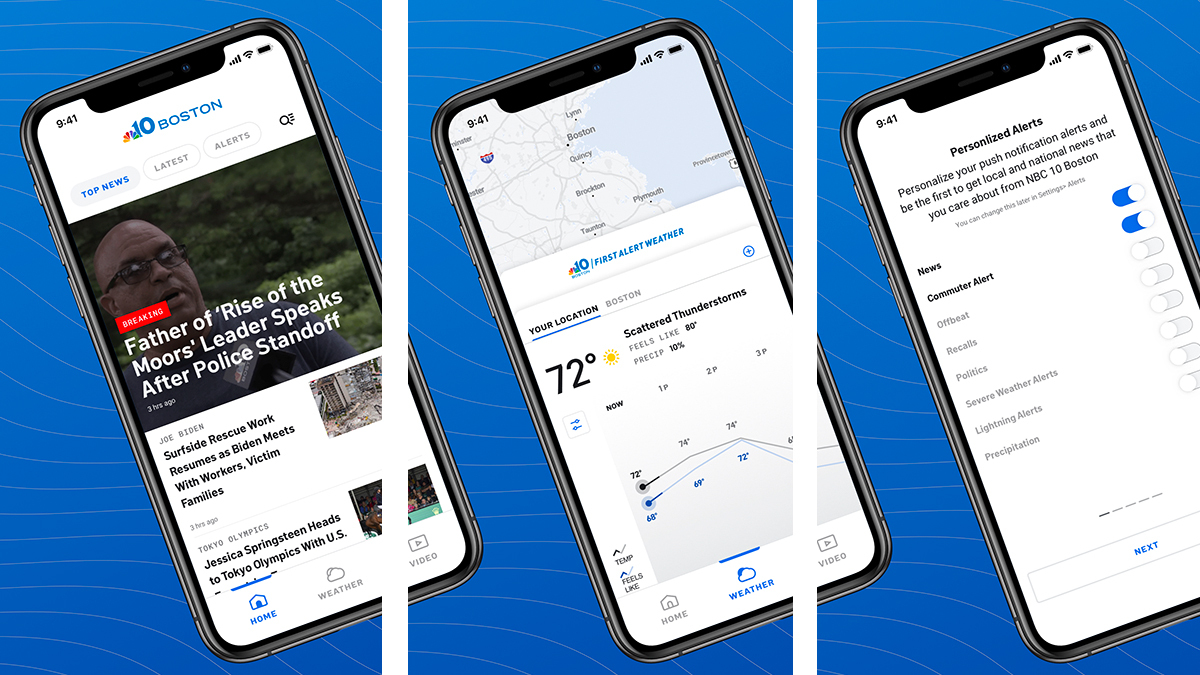

Get Boston local news, weather forecasts, lifestyle and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC Boston’s newsletters.

Olympic organizers banned all spectators from the games this year after Japan declared a state of emergency meant to curb a wave of new COVID-19 infections.

It was the latest setback for the 2020 Olympics, which have already been delayed for a year, forcing athletes to begin training all over again. And without any international tournaments or competitions during that time, fencers like Dershwitz are heading into the games with less scouting on their competition.

“It's going to be a little bit more of a guessing game,” Dershwitz said. “It's going to come down to, you know, how well we pair individually, how mentally and physically ready we are. How much you're willing to fight at the games for a shot at making history.”

Anyone entering Japan for the Olympics was required to follow complex testing rules before leaving home and after arriving. Athletes also agreed to have their location monitored by GPS, downloaded several apps and signed a pledge to follow the rules. They must maintain social distancing, stay off public transportation for the first 14 days and keep organizers informed of their whereabouts while in Tokyo.

In addition to those procedures, the stringent pandemic restrictions strip athletes of opportunities to gather, socialize in the Olympic Village and explore the host country.

“I'm going to miss this year getting together with all the athletes at the Olympic Village and then getting transported over to the main stadium, you know, waiting to march into the stadium. That is incredible,” four-time Olympic dressage competitor Steffen Peters said. “That is extremely inspiring, and I think inspiration is one of the biggest gifts of humankind.”

Don’t miss the most exciting moments of the Winter Olympics in Beijing! Sign up for our Olympics newsletter.

Peters, a German-born equestrian who became a U.S. citizen in 1992, described past games where he met and took photographs with Michael Phelps, the most decorated Olympian of all time, and Klay Thompson, one of the greatest shooters in NBA history.

For first-time athletes, like 18-year-old archer Jennifer Muciño-Fernandez, the enthusiasm is still there, but with a touch of wistfulness. Born in Brockton and raised in Mexico City, Muciño- Fernandez came back to the U.S. to train for her Olympic dream, which began when she was just six years old. Twelve years later, that dream is coming true, albeit different than she imagined.

“I'm so excited, I am a little bit sad that the Olympics are taking place in, you know, this very difficult year,” Muciño- Fernandez said. “I feel like we are going to be losing a whole bunch of experiences. So much is going to be lost due to the restrictions.”

Fundamental changes to the nature of the Games - like the empty stands - can be an added challenge for athletes like Muciño and Dershwitz, who thrive off the energy from the crowd.

“I remember... that electric atmosphere, you know, having my college friends, my hometown friends and family there - it's just a surreal experience,” Dershwitz said. “It's really going to come down to how mentally strong you are as an athlete to be able to adapt to these new situations, you know, in just a few days.”

“The crowd helps you; like, it’s very different to have people supporting you. It’s very, very fantastic – that feeling,” Muciño said.

But the impact of not having spectators varies depending on the sport. It can even be considered an advantage in some cases, Olympic dressage competitor Peters explained.

“Usually a dressage fan is pretty quiet at the stadium, because they know horses might react to some excessive noise,” Peters said. “So, even then if there would be some noise, I'm able to tune that out. Of course, you know, it would be nice if our horses do the same. That's not always the case. So, for the horses, it is actually better if it's a less electric atmosphere.”

Despite the restrictions, athletes had a positive attitude and respect for the decisions made by officials and the Japanese government.

“I truly believe, if you go to Rome, you do it the Roman way. If you go to Japan, we do it the Japanese way. We have to respect the culture. It's a culture that's very, very strict in their rules,” Peters said. “On top of that, I really trust the rules of our federation. They're so extremely well-organized and have prepared us so well for every single scenario regarding testing. So, no, I'm not nervous about it. I trust our federation, and I respect the Japanese culture.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Tokyo Olympics

Watch all the action from the Tokyo Games Live on NBC