It’s not the first time this winter this has happened: forecasts, uniformly, have been great for some, but way off for others, often just a few towns or even miles apart.

In our Tuesday nor’easter, we even saw snow totals spanning a range of as much as eight inches just from one side of town to another!

The tried and true response of, “Weather in New England is hard to predict” just doesn’t cut it in instances where some communities fall as much as half a foot shy of predictions, as was the case in this March nor’easter for parts of northeast Connecticut, northern Rhode Island and suburbs south of Boston.

Get Boston local news, weather forecasts, lifestyle and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC Boston’s newsletters.

Inaccuracies are more than just numbers: they are school kids and parents thrown off routines, snow clearing operations improperly prepared and businesses that depend on accurate weather predictions left to scramble and re-organize.

The question arises in storms that feature huge differences in amounts: how can weather forecasts be so wrong for some areas, but so right for others, in 2023?

Some harken back to a time, decades ago, when computers were used less for forecasting and it seemed the forecasts were better. That idea waxes nostalgic and pays tribute to the greats of New England forecasting, but is factually incorrect: verification scores unquestionably show a vast improvement in forecast accuracy with passing years. We have, put simply, raised our expectations for accuracy as a community with the advancing science of meteorology.

One idea is perhaps either the meteorologist didn’t try hard enough, or simply was incompetent at the job. The problem, of course, is the inaccuracies for the few storms that have featured errant forecasts this winter is the mistakes have been industry-wide: forecasts may differ by a couple of inches here and there, but the areas that are missed have generally been missed across the board, which implies something more systemic.

Be prepared for your day and week ahead. Sign up for our weather newsletter.

Here’s the scientific insight: It’s not imagination – this winter absolutely has featured more unpredictability than most. The mild winter, with a lack of deep cold air, has meant marginal temperatures for rain and snow, time and again.

If elevation were the only factor that matters in a setup with marginal temperatures, it would be fairly straight-forward: base the forecast entirely on how high up a location is. What this mild winter has demonstrated very clearly, however, is the science of meteorology still has much work to be done — research, technology and application — on understanding the delicate and critically important interaction of near-surface temperatures, solar radiation, ground temperatures and precipitation intensity with snowfall accumulation.

Near-surface temperatures are important because snow can survive a trip through temperatures above freezing and still accumulate … but only within a few degrees. Of course, the temperature of the ground on which it falls is important, which is why spring snow can accumulate much quicker and easier during the day if it’s falling on snow that already coated the ground at night, before the sun came up.

Sun strength is rapidly increasing this time of year and is equivalent to that of October sun, which has a huge impact on the temperature of both land and objects. All of these factors can be overcome by heavy enough precipitation, when snow falls heavy enough to offset the other players.

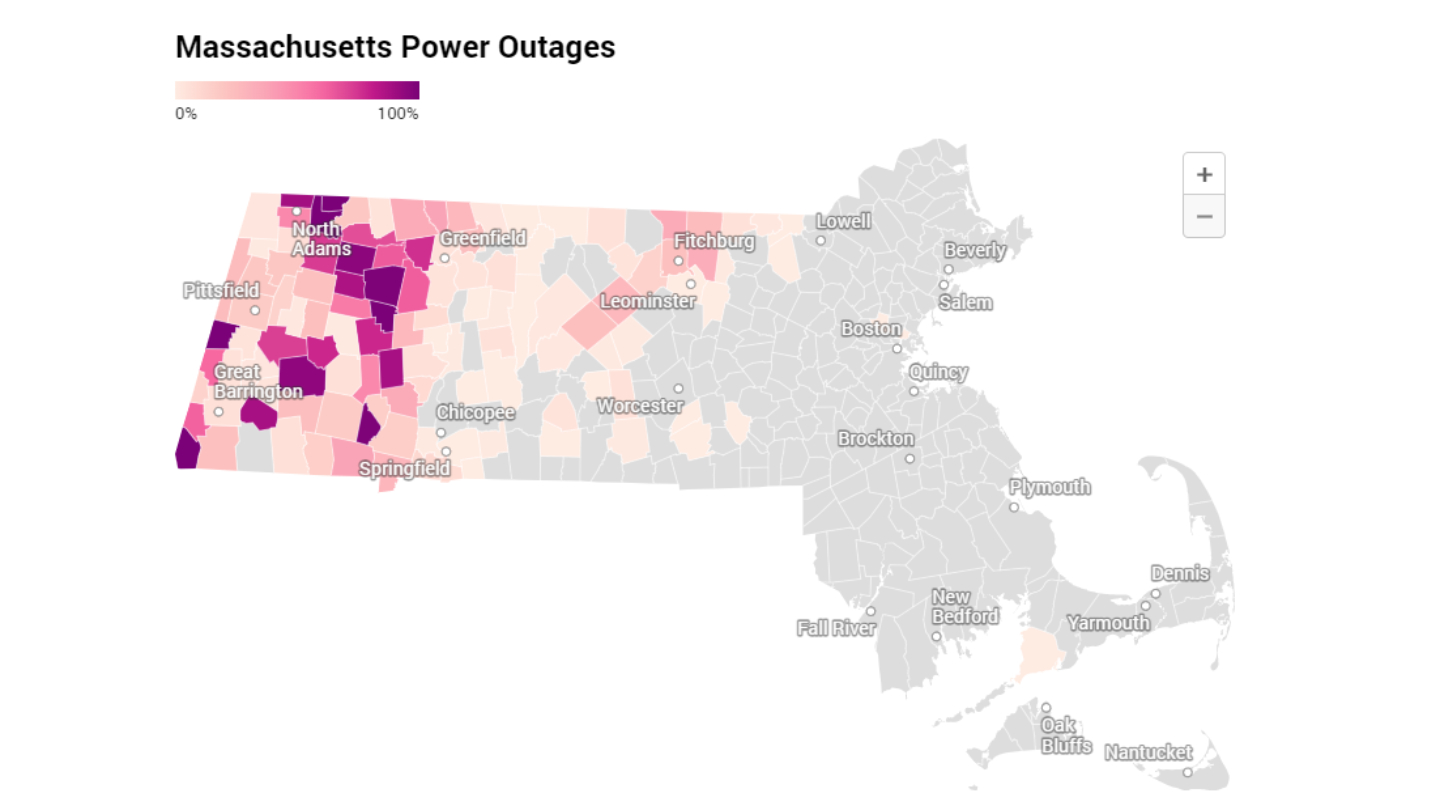

The bottom line: when looking at the incredible difference in amounts over small areas with some of this year’s storms — and the incredible lack of snow for some vs. prediction — we just haven’t reached that level of accuracy for these particular, marginal temperature cases yet.

So how do we fix it? The honest answer is it will take years. Case studies, research, application and execution are all part of a scientific process, and meteorology is very much a science, rooted in math and physics.

Get updates on what's happening in Boston to your inbox. Sign up for our News Headlines newsletter.

Of course, this doesn’t mean every storm forecast is destined to go down in flames for years on end — we’ve become accustomed to good accuracy, and that’s why it really stands out when the forecast misses.

The vast majority of forecasts will continue to be good, but these marginal temperature cases will pose problems, and with mild winters becoming more common, that means we have most certainly not seen the last of these issues in the years ahead.

If you find yourself frustrated, there is action that makes a difference: support STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) education for children and support scientific research at the private, university and government levels — this is the future of science in America.

On our end of it, we’ll continue to explore, experiment and revamp, learning from cases where the forecast goes right … and wrong … to continue improving our First Alert Forecast, already certified as most accurate in Boston television, but most accurate certainly doesn’t always equate to perfect — and perfect is always our goal.